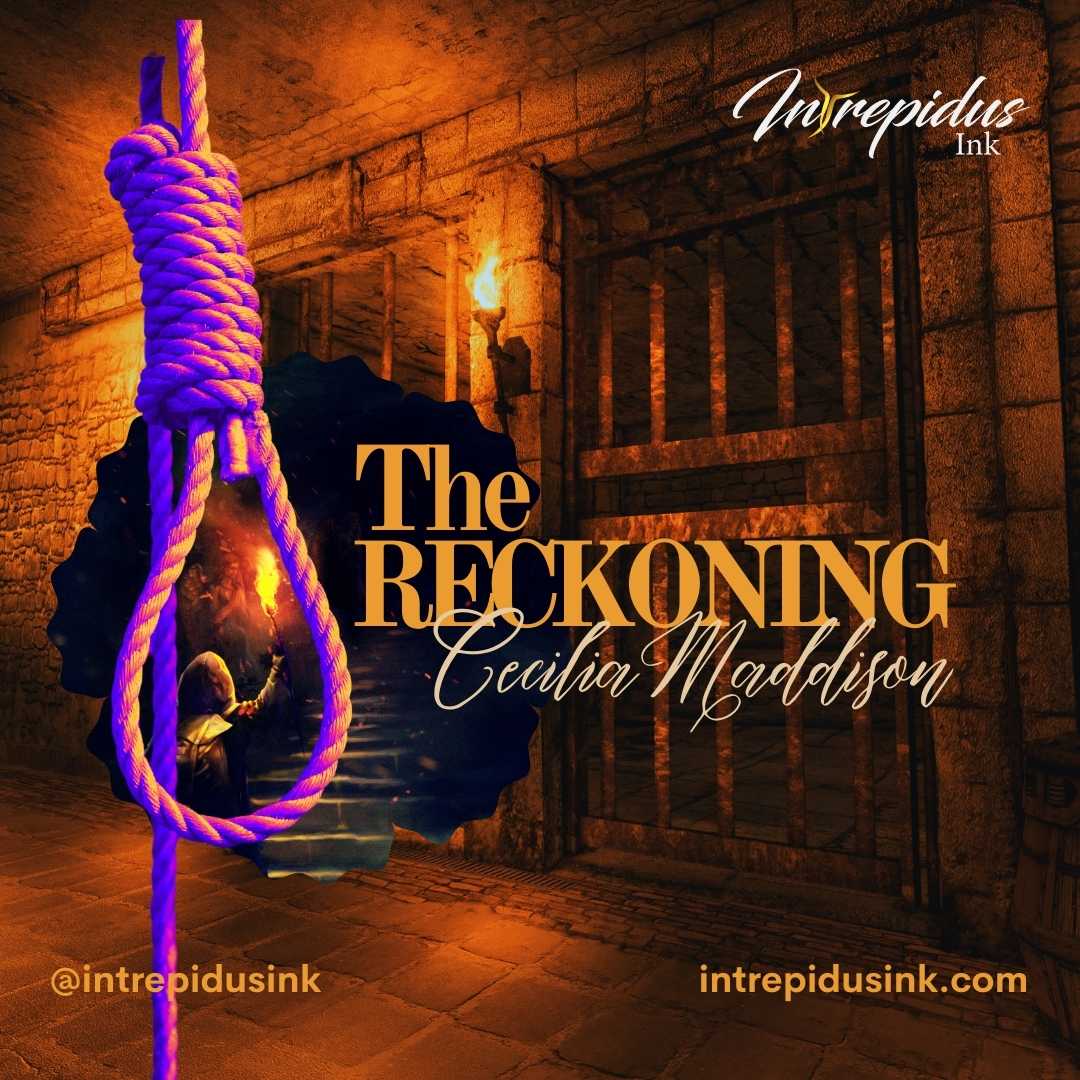

Action Adventure

I saw my first hanging in Wapping when I was four years old. My father swung me up on his shoulders so I could see across the rabble of spectators. The prisoner was a scrawny youth accused of stealing a gentleman’s horse, and as they dragged him to the gallows, his britches darkened with piss. I squeezed my eyes shut and buried my face in the hair on my father’s head.

“Watch,” my father urged. “Only cowards look away.”

Peeking through my fingers, I looked up in time to see the youth drop. His limbs jerked to a merry tune I couldn’t hear above the crowd’s roar.

But I’d never seen someone from our village hanged, and my stomach churned to think of Mabel’s frail old body dangling at the end of a rope. For as long as I could remember, her basket had held salves for my scraped knees, and all year round, her cottage smelled of summer from the dried herb posies strung from the rafters. I’d helped her tend to her bees and set traps for the rabbits that nibbled her garden greens, and in return, she’d served me bowls of sun-warmed fruit and cream. Mabel didn’t belong in the makeshift gaol set up in the cellar of my father’s inn. Only drunks with loose fists had been locked in there before. Yet when the travelling witchfinder Matthew Hopkins proclaimed her guilt, no one opposed him.

The night before Mabel’s execution, I crept down the cellar stairs to see her one last time. She lay slumped in a miserable heap against the wall.

“Are you scared?” My whisper rustled through the shadows and flickered the single candle’s flame.

Mabel raised her head and fixed her bloodshot eyes on me. Strands of grey hair had worked free from her cap and plastered her cheeks.

“No, William. I’m not scared. I’d rather hang than suffer another day.” She lifted her hands, rattling the iron links around her wrists, and studied the bruises blotting her arms.

I opened my mouth to ask another question, but the words stuck in my throat.

“Go on,” she said.

“Is it true you’re a witch?”

“Women like me are called many things that aren’t true.”

“But can you change shape? Goody Winthrop claimed she saw you drop to the ground like a rabbit and tear across the fields.”

Mabel snorted. “Goody’s been soft in the head since her husband died. She agreed with every daft notion that Mr. Hopkins put to her.”

“Then why are they going to hang you?” I rubbed my eyes to stop the tears because, at twelve years old, I was almost a man.

“The village has been fooled, lad. The devil’s made no pact with me–he’s too busy whispering into Mr. Hopkins’ ear.” Mabel spat out a mouthful of blood and wiped her lips on her shawl. “The devil’s filled his head with pomp and filled his mouth with blather. Folk should fear him, not me, but they’re swept away by his fancy words and trickery.”

Above us, the cellar door groaned, and my father’s heavy tread creaked on the wooden stairs. Mabel pressed a finger to her lips, and I slipped into a corner. I peered around a barrel’s edge, holding my breath.

“Mabel.” My father set his lantern on the floor and pushed a bowl of stew towards her. “This is from Alison. She’d come down herself, only Mr. Hopkins needs waiting on.”

It was a half-truth. My mother was busy attending to Mr. Hopkins’ hearty appetite for wine and mutton. I’d also heard my father give strict instructions for her to maintain a distance from Mabel. “No need to be tarred by association,” he’d said.

Mabel held out her shackled hands, and my father unlocked them with a key tied to his belt. She rubbed her wrists and seized the spoon with trembling fingers. “Strange to find I’m hungry when my neck’s to be noosed in the morning,” she said between full mouthfuls.

“It’s a bad business,” said my father. “I can’t deny you’ve been good to us over the years. Your herbs cured Alison’s fever after her confinement. You sat up with us all night when Will was half-dead from sweating sickness. I’ll not forget that.”

Mabel stopped eating. “I’ll not forget you looked away when Mr. Hopkins set upon me with his ducking stool and pricking tools. I’ll not forget your silence when he swore that I’m behind the failed crops. He speaks nonsense. Charmed the sense from every head he has! Swindled you all out of twenty shillings, too. Fools, the lot of you.”

“I don’t know about that.” My father’s cheeks flushed. “Mr. Hopkins is a learned man with books and papers. He’s backed by Parliament, too. Who am I to question the science of his trade? They say he tried three witches in Bishop’s Stortford, and their cattle’s distemper resolved overnight.”

“You always were a weak man,” Mabel pushed the unfinished bowl of food away. She held out her arms, and my father re-fastened the chains.

“Mr. Hopkins is a man of his word,” my father said through gritted teeth. “He’s promised not to take a farthing if he doesn’t find and foil a witch. God knows folk need some hope around here, and he’s sold us some.”

“You’ll follow him to Hell,” Mabel called after my father’s retreating figure.

When the cellar door had thumped shut, I edged back to her side and tugged on her shawl. “I’m sorry,” I told her, full of remorse for my father’s failings.

Mabel didn’t stir. “Get going, William. You’ll be whipped if you’re found here.”

I loitered, scuffing the toes of my boots against the dank flagstones, undeterred by the thought of my father’s birch strap. The candle, already burned down to a stump, sputtered by the time I took my leave.

#

Mr. Hopkins kept late hours, for it was after midnight by the time he finished his remarkable accounts of witch finding in neighbouring counties. “The proof lies in my method of pricking,” he concluded, waving a finely tailored sleeve. “Confession follows, without fail. Rest assured, when the hag is hanged in the morning, the village’s bad fortune shall be reversed.”

When he and his fellow patrons had retired, my father kept counsel at their empty table, drinking himself into a stupor. The key at his side glinted in the firelight.

“What are you still doing up?” he grumbled when he found me skulking near his feet. He flung his hand out in a lazy bid to rap my skull, missing me by a yard.

“I’m not ready for sleep.”

“Nor am I, son.”

“How can Mr. Hopkins be sure that Mabel’s a witch?”

“He proved it with tests. You saw for yourself that she couldn’t be drowned in the river.”

“The current swells upwards when it passes that bend.”

“He pricked her and cut her, and she wouldn’t yield a drop of blood.”

“Her mouth bled where he broke her tooth.”

“Mabel admitted she’s a witch. She signed a confession.” My father averted his eyes from my face and drained his cup. “Mr. Hopkins vowed to stay until his work is done. Best let this matter run its course so he can take his leave.”

I refilled my father’s cup to the brim and watched him drink until his eyelids drooped and his chin sank to his chest.

#

My father slumbered all night in his chair. At daybreak, I shook him awake and set about helping my mother prepare morning victuals for our guests. My father sat by the fireplace, nursing his head in his hands until Mr. Hopkins sauntered downstairs with the ease of a man well-rested.

“The witch will face her reckoning today,” Mr. Hopkins declared, his lips glistening with grease from the platter of cold meat I’d set before him. “And what a fine day for it. She may squirm and protest all she likes, for the crowd loves a commotion.”

“Perhaps she’ll go quickly, sir,” my father said. “She’s old. It won’t take much for her neck to snap.”

“We’ll see,” said Mr. Hopkins, dabbing the corners of his mouth with dainty fingers.

By mid-morning, revellers were assembling at the crossroads outside the inn, and whilst I picked out some local faces, many more had been pulled in from afar. Through the window, I watched men appraise the freshly assembled gallows, slapping the posts and tracing the rope with pointed fingers. Women clustered, gossiping behind cupped hands, scolding children for spattering mud as they played. When my father threw open our doors, a surge of people poured in, clamouring for ale and for a sight of Mr. Hopkins, whose puffed chest strained the seams of his shirt.

“It’s time,” Mr. Hopkins announced, beckoning for my father. “Fetch her.”

I pressed through the throng, squeezing through legs and under elbows until I stood behind my father. He swung open the cellar door, lantern aloft, fumbling for the key at his belt as he descended the stairs. The crowd hushed. A muffled curse sounded from the cellar’s depth, followed by my father’s hurried footsteps. He reappeared, his face dazed and his arm raised. From his fist dangled a rabbit, held fast by its feet. It thrashed and bobbed, its body writhing as it tried to break free. But my father’s grip was firm, and the rabbit was weak.

“Mabel’s gone,” he told the stunned crowd, holding up the frantic creature. “The cellar’s empty, save for this, caught up in her chains.”

“Impossible,” muttered Mr. Hopkins, blanching. The corner of his eye twitched.

I scrambled onto a chair and filled my lungs. “Witchcraft!” I exclaimed, pointing at the rabbit. My voice, shrill and clear, cut through the astonished gasps. “Mabel’s changed shape!” I pointed back to Mr. Hopkins. “You were right, sir. Look, everyone–it’s just as he proposed. The witch has turned herself into a rabbit!”

The uproar shook the rafters, rippling through the inn to the street outside. Mr. Hopkins raised his hands, demanding order, but his voice was lost in the tumult of shouts and screams for the wretched beast in my father’s hands to be killed.

#

The woods were still and solemn, as if time itself was resting. Brambles snagged my shins, drawing beads of blood from where I’d trampled through them in haste. Although the last of the day’s sunshine pierced the canopy, the air was cool. I spun around, scanning the shadows.

“Hello?” I murmured. A bird chattered in alarm as it flew from the nearby undergrowth.

“Over here, William.” Mabel emerged from a dark green shimmer of holly leaves. The woollen cloak draped over her shoulders lent her the look of a bird, and her hair, entirely loose, waved in grey tendrils about her shoulders.

“Mr. Hopkins said we’ll not be troubled by witchcraft again. He claimed his silver and left in a hurry,” I told her.

“I’m sure he did. God help the poor souls he’ll be after next. But I sense his time is running out.”

“I can’t stay long. The inn’s heaving, and I’ll be missed. I brought you this, though.”

Mabel took the bundle I held out, unfolded the cloth, and breathed in the aroma of the cheese and ham I’d filched from the larder. “Wonderful. Thank you, my boy.”

“Will you be alright?”

“I will. I’m safe here, amongst the trees. And what about you?”

“My father’s suspicious.” I deepened my voice into a gruff imitation of him. “‘If I didn’t know better, I’d wager that rabbit was freed from a trap while I was asleep.’”

Mabel laughed. “He won’t trouble you. He’d rather not see what doesn’t please him. But look, you’re shivering, lad. You’d best get on your way.”

We bade farewell with an embrace, and it seemed to us both that I stood taller than before, as if I’d grown in the last few hours. At the woodland’s fringe, I turned around one last time, squinting to make out Mabel’s slight figure amongst the ancient oaks and elms.

“It’s my father who taught me what to do,” I called out, watching her melt into the gloom. “You see, only cowards look away.”

Author Bio

Cecilia Maddison is a writer from London, UK, where she works as a health professional. Her flash fiction and short stories have been published in Brilliant Flash Fiction, Bright Flash Literary Review, The Ulu Review, Raw Lit, Stories That Need to Be Told (Tulip Tree Press 2023), and Soulmate Syndrome: Certain Dark Things (Wicked Shadow Press 2024).