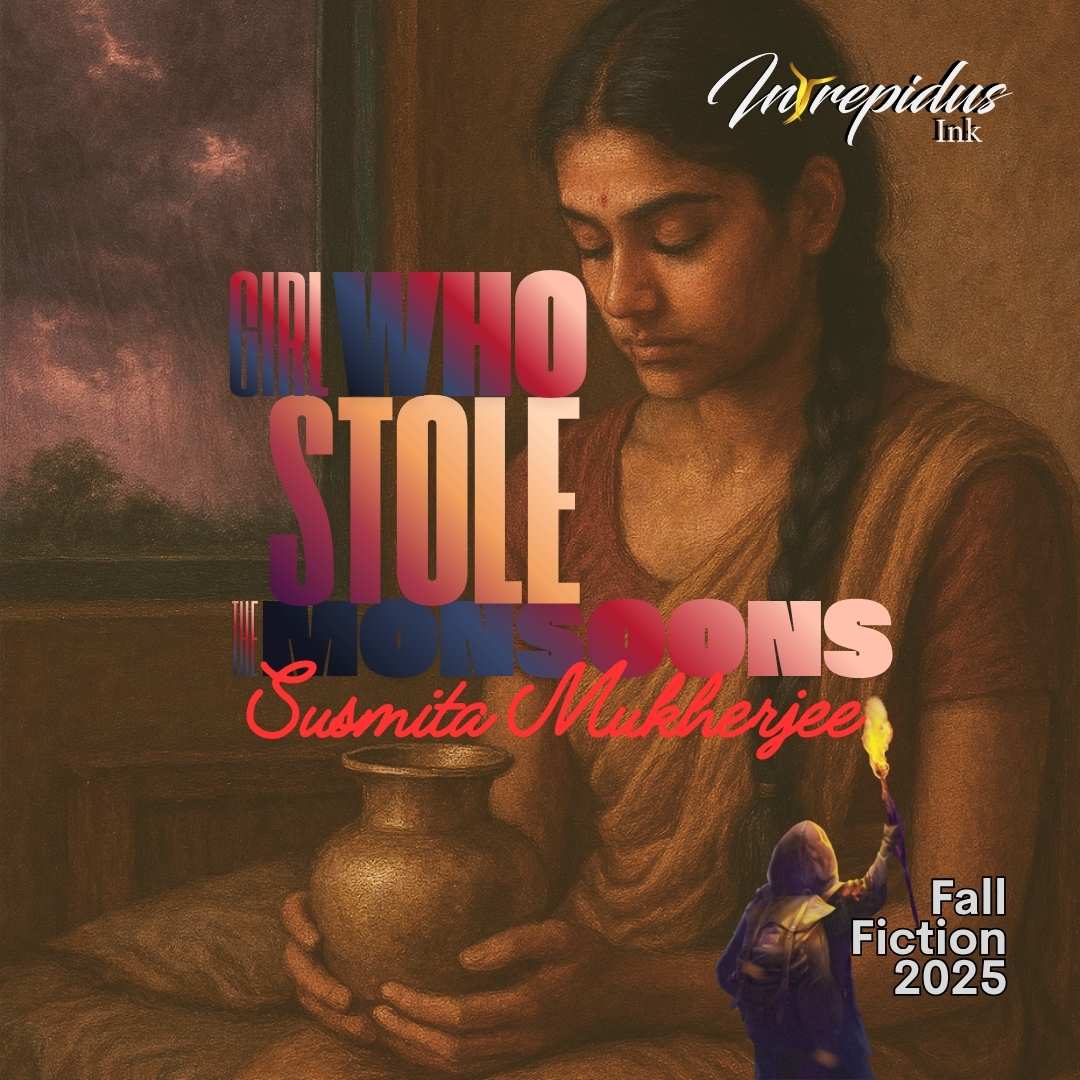

Magical Realism

When the monsoon failed to arrive that year, the people of Ghoshpara began to mutter beneath their breath that someone had stolen the clouds. The ponds cracked into mirror-shards, the frogs turned mute, and the banana leaves drooped like weary hands. Only one person seemed untouched by the heat: little Mita, who walked barefoot to school every morning with her hair wet as if she had bathed in rain no one else could see.

Mita lived with her grandmother in a tin-roofed house by the railway line. Her parents both had drowned the year before, her father in the Hooghly River trying to save a neighbour’s son, while her mother three months later when her ferry capsized near Chandannagar. Since then, Mita had become quieter than a shadow, though sometimes, her grandmother said, she would be found talking to puddles that weren’t there.

The villagers pitied her, for she became thin and strange, and carried an old brass lota to school every day, although she never drank from it. The other children teased her, saying she collected ghosts. Mita never answered. She simply smiled that faraway smile that belonged to someone who had seen what others had not.

One afternoon, when the schoolmaster fainted from the heat and the children were dismissed early, Mita took the path behind the mango orchard. The earth was parched, the air buzzing with cicadas. She sat under a tamarind tree and mumbled into her lota. If anyone had been there, they would have heard a faint gurgle like distant thunder rolling across the sky.

That evening, thunderclouds gathered over Ghoshpara for the first time in months. People stepped outside their houses, faces lifted, palms open, waiting for the first drop. But the clouds drifted past, carrying their promise elsewhere. Only Mita returned home drenched.

“Where did you get wet?” her grandmother asked, wringing her hair. “There’s no rain.”

“There is,” Mita said softly. “But it’s shy.”

That night, the grandmother dreamed of her dead daughter calling from a river, “Ma, don’t worry about Mita. She’s learning to bring me back.”

Over the next few days, strange things began to happen. Mita’s garden turned green overnight. The dry hibiscus bloomed crimson, and mushrooms sprouted from the cracks in the walls. Each daybreak, dew shimmered on her windowsill even though the rest of the village lay baked in dust.

People began to visit the grandmother’s house with offerings, flowers, coconuts, and questions. They asked whether Mita could help call the rain for everyone. The grandmother, both proud and frightened, said, “She’s just a child. She plays with wind and words, that’s all.”

But Mita overheard them. That night, she sat before her lota again, murmuring to it, her eyes shining in the lantern light. “Come back,” she said. “Come back for everyone.”

She placed the lota outside her window and fell asleep to the sound of something sloshing inside it.

The next morning, the sky was swollen with clouds. The wind smelled of wet earth and rusted train tracks. But the first drops fell only in Mita’s courtyard, a perfect circle of rain no larger than a pond. Children gathered around, holding out their hands. The rain wouldn’t cross the threshold.

“She’s keeping it for herself,” someone muttered. “The little witch.”

The harsh words twisted Mita’s heart. She hadn’t meant to be selfish. That night, she cried into the lota, and the water rippled seemingly to comfort her. When her grandmother found her sleeping beside it, her cheek pressed to the cool brass, she seemed to hear the faint echo of waves.

The very next day, Mita was gone.

Her bed was empty, her schoolbag still beside it, and her shoes by the door. The lota lay overturned on the floor, spilling a thin stream of water that seemed unending. It trickled through the courtyard, through the bamboo fence, out into the dusty lane, and wherever it passed, the earth softened, darkened, and breathed again.

By noon, it reached the pond at the edge of the village. By evening, the pond had swelled and spilled over, and frogs croaked like drummers at a festival. The sky commenced to overcast, a canvas of deepening grey, dense and heavy.

Eventually, when the first true rain came, thick, silver, drenching, the villagers believed they heard a girl laughing among the thunderclaps.

For three days, it rained relentlessly, filling the canals and washing the courtyards clean. Women sang from their verandas, children floated paper boats, men stood shirtless under the downpour, faces lifted skywards in gratitude.

But when grandmother searched the fields and rivers for Mita, she found nothing. Not even a footprint.

At dusk, she returned home, her saree soaked, her eyes hollow. The house smelled of damp earth and mango leaves. The brass lota rested on Mita’s bed, half full of rainwater, gleaming softly in the lamplight.

She lifted it with trembling hands. Inside floated a single strand of her granddaughter’s hair.

Her grandmother wept for the rest of the night. Yet when she went to pour the water out, she couldn’t. Something in her heart told her to keep it safe. So, she placed the lota by the window, where the lightning could see it.

The monsoon lasted longer that year than anyone could remember. Fishermen said the river was more generous; farmers said the rice fields sang louder. When strangers asked how Ghoshpara had survived the drought, the villagers told the story of the girl who stole the monsoon and gave it back to them.

Years later, when her grandmother passed away, the lota was found beside her bed, sealed with a red hibiscus inside. When they lifted it, a drop of water spilled out and hit the ground.

And just for a moment, before the sun burned it away, it smelled like rain.

Fall Fiction 2025 Spotlight

Author Bio

Susmita Mukherjee is a Kolkata-based author whose fiction, poetry, and essays explore memory, silence, and the inner weather of human lives. Her work has appeared in Indian Literature (Sahitya Akademi), Sky Island Journal, BULL, Literally Stories, and Kitaab, among other publications. Her debut poetry collection, When the Earth Sang of Us, is available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.