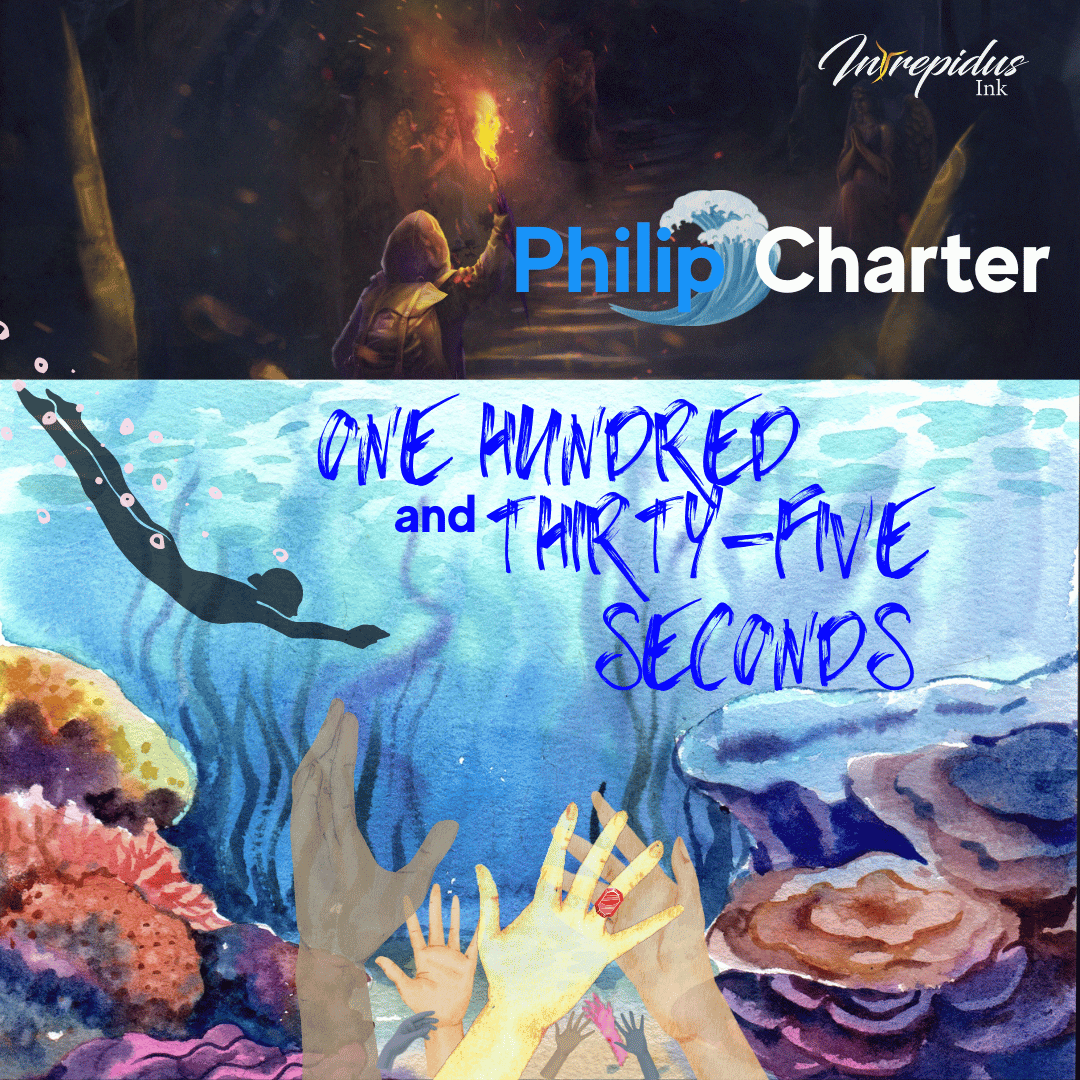

Literary Speculative Fiction

B

reathe deep and break the surface. Ice blue waters tingle on lips. Your arms pull like longboat oars, thrusting you down.

Since childhood, you’ve explored every inch of the seabed in front of the beach house, searching for your lost twin, your fingers brushing gray-black sand, which whips into underwater storms. You’ve toughened against the cold, even though your skin runs taut on your bones. No gloves or balaclava, just fins and a rash vest.

Your parents used to look on, proud, as you waded into foaming waves. “Not past the step,” they’d say. “Never past the step.”

Now there’s no one to stop you from visiting the exact spot it happened, touching the bones. That time, you made it back.

The step is an underwater cliff that drops deep. After the lobsterman charted the seabed with his sonar, you calculated it takes one hundred and thirty-five seconds to touch the bottom and swim back up.

Under the waves, it’s calm. Fins flow and you glide. In just over a minute, you’ll know what’s at the bottom of the jagged black wall. A thousand tiny fires light your lungs, and pressure mounts as thousand-ton walls push down. Just one glimpse of the bottom, you think, then back to shore. In the depths, the weakened sun lights flotsam swirls. The sandy dark approaches.

Two strong kicks and you touch. A fistful of volcanic grains to take back as a prize. You’ll burst for air and punch the sky. They’ll weigh about the same as a floating child. As you turn, a movement grips you. You freeze. A few yards farther out is a human hand, fully formed, attached to the seabed. It sways in motion with the water.

Your own hands are cracked, and your nails cling to the ends of your fingers. They don’t feel the cold. After the drowning, you stopped handling the shells in your collection. The only ones you wanted to touch were at the bottom.

Two minutes gone. It only takes a few kicks to get close enough to investigate. It’s not just any hand. It has the liver-spotted skin of your mother’s. The ruby ring is unmistakable. Although you don’t tell it to, your arm reaches out. When you touch, the sea hand jolts into life as if the sensation woke a brain in each of its bony fingers. You’ve trained for this. Another ten seconds. Interlock fingers. Clasp. Ride the ebb of the undercurrent.

The darkness clears, and for a split second, you see a whole field of hands reaching up. Hundreds of them. The delicate fingers that brushed your arm at a party and the swollen knuckles of a businessman that crushed your grip.

The dying oxygen in your lungs means nothing. You could float forever in this strange museum of hands. As you pass over, they move with you, following your path. Some are muscular and some are withered. One has a finger missing from a fishing accident. Some wave, others beckon.

And then you see it. The one. This is the reason you held your breath for over two minutes, three times a day. This is the reason you waited until you could blow a 700 on the peak flow test. If you could take your diver’s knife and cut your hand at the wrist to leave it there, you would. You would.

It must be nearly three minutes now, but you go towards it, not up. Darkness steals the corners of your vision. Reach. Connect. Feel the heat contrast years of silence.

It’s only twenty seconds to the surface. Twenty seconds of pain before you breach, gasping salt air. But you stay. The seconds tick and the ocean vice tightens around your chest. They say the moment before drowning is a mixture of agony and euphoria.

And then, release. The hands detach. They float and swarm. Each one finds your body, gripping loose fabric, bunching strands of hair. You feel them supporting your weight, pulling you up, back through all the years you held your breath until you reach the place where sea meets air.

An Interview With Philip Charter

Intrepidus Ink: Your background is fascinating—historian turned world traveler 🌎 and language coach eschewing the bonds of a 9 to 5 role. ✅ How does your fearless approach influence your words?

Philip Charter: The places I travel are my inspiration and often form the seed of a story. I grew up by the sea and now live in Gran Canaria, only five minutes away from the Atlantic Ocean, so I suppose the pound of waves is embedded in me somewhere. I guess I needed to write a story about the liminal space between land and sea and “One Hundred Thirty-Five Seconds” is it.

II: Traveling the world defined you as a language coach. 🤿✈🏝 Will you share more about that experience?

PC: I began writing fiction when I left the UK (around 2011) and it’s no coincidence. As I lived in Latin America for some years, I learned Spanish, which gave me a new joy for language and sparked my creativity. I can’t recommend learning a language enough – it really opens a lot of new pathways and thought patterns. And now, I help multilingual writers navigate the world of working in English. I learn something new every day, and try to impart that knowledge to others. So the cycle continues….

II: Your stunning webpage showcases your work as an author and international language coach. 🤩 With two collections of short fiction and a Pushcart Prize nomination, what’s next for you? 👂

PC: I’ve got a lot of diverse projects on the go! I’m editing the world’s first bitcoin fiction anthology (due for release in 2023) and am doing some work with a new publishing platform, Storya. Apart from that, I’m hoping to publish another novella-in-flash and am working on a novel about sea lore.

II: And you know what? We’ll be cheering every word because we’re fans for life. 🙌 Best wishes in all you do. 🌍

Author Bio

Philip Charter is the author of two collections of short fiction and Fifteen Brief Moments in Time, a novella-in-flash. In 2021, his story The Fisherwoman won the Loft Books Short Story Competition and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He escaped the bad British weather in 2011 and now lives in Spain. Please visit his website.

1 thought on “One Hundred and Thirty-Five Seconds”

Since discovering this gem of a mag, I’ve looked forward to each new story.

Now it’s finally my turn. Thank you for publishing my work.

Comments are closed.