Action Adventure

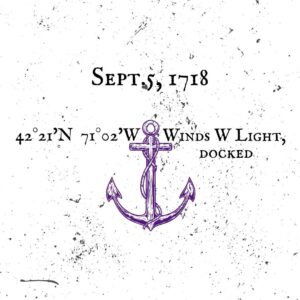

Rachel sneaked aboard at six bells, deep in the night. The ringing masked her tread. The snores of the sailors cloaked her steps, but still, the floorboards creaked. She thought of her sister, held hostage behind the cold stone in Boston Gaol. Rachel steeled herself. She had to get to Nassau.

#

The Margaret slipped her moorings just before dawn, trailing the tide out of Boston Harbor. One hundred souls, two hundred tons, more than one secret. The call and response of the Shanty Man’s song rang throughout the ship. Lines creaked, sails snapped, sailors swore, then water streamed past the hull. The Margaret sailed for Bath, North Carolina, inside the treacherous shoals of the Outer Banks. The first day was calm.

Rachel’s hideaway was comfortable until the weather came up out of the south. She’d eaten all her food, and she had to pee. The seas ran high, and the ship pounded through the waves, hitting her right in the bladder. The ship’s cat, more observant than the crew, found her at nightfall.

On day three, Rachel decided it was too late for them to turn back and mounted the companionway to meet her fate.

Captain Nathaniel Sewall was a slaver but by his own lights, not a villain. “Now, you’re a mess of trouble and no mistake,” he said, “but I won’t throw you overboard. Stand there by the Shanty Man. Stay out of the way.”

The captain nodded at a short, very dark man sitting on deck under the mainmast. The man had battled the sun for decades and lost. Tattoos writhed up his arms, fantastical creatures that emerged from under his shirt and climbed onto his face. He watched her like a feral cat might regard a fish.

“Stand here, child. I won’t bite–yet,” the man said. “The ship needs me now.”

He launched into song.

Now we’re ready to head for the Horn,

Way hey, roll and go!

Our boots and our clothes, boys, are all in the pawn,

To be rollicking Randy Dandy-O!

Heave a pawl, heave away!

Way hey, roll and go!

The anchor’s on board and the cable’s all stored,

To be rollicking Randy Dandy-O!

As he sang, sailors heaved on lines, and the sails obeyed their commands. Rachel, mesmerized, had no idea what they were doing. She’d never been on board a ship.

“You ain’t near scared enough,” the man said. “Whatcha doing here?”

“I’m making my way to see my mother down in North Carolina.”

The Shanty Man snorted.

“You got a better story, or you gonna stick with that’n?”

Rachel said nothing. The Shanty Man just laughed.

“What’s a chanty man?” asked Rachel, ever curious. “What does that song mean?”

“Not chanty. Shanty. Shanty’s a sea song. Different kinds for different jobs, different seas. I know the jobs, the songs, the seas. I’m the Shanty Man. You think the wind moves the ship, but it’s me. Them songs have sea magic.”

A hunger stirred in Rachel.

“Would you teach me one of your songs?”

The Shanty Man looked at her skeptically but took in the long brown hair, fair face, and full figure. He’d been at sea a long time.

“How old are you, girl? Not that it matters.”

Rachel was thoughtful for a moment.

“Seventeen, maybe? I don’t really know. But I learn fast. Teach me?”

The Shanty Man swept his eyes over her again, smiled, then silently returned his attention to the ship. Rachel had seen that kind of smile on men’s faces before. She waited for lust to overcome his caution. As they sailed, he leered at her but kept his hands to himself. Stowaways weren’t unheard of, but a young woman—that didn’t happen. She reckoned he couldn’t figure her out.

The truth was beyond his ken. Rachel was a spy.

Rachel and her sister Ruth were orphaned in Boston, and they’d turned to crime to eat. More dauntless than adept, they’d been caught. The Governor’s men brought Rachel to Captain Cyprian Southack, the Governor’s pirate hunter, a short, grim man. Southack’s orders were to do whatever it took to bring the pirates down. The Governor would ask no questions about his methods.

“Ever hear of Anne Bonny?” Southack asked her.

Afraid, mute, she shook her head no.

“Mary Read? How about Blackbeard?”

Blackbeard, she knew. Why was he asking about a pirate?

“Bonny is a pirate. A woman,” said Southack. We’re trying to get a spy onto her ship. The men we sent were never heard from again. I’m thinking maybe a woman has a better chance. Send a woman to catch a woman, something like that.”

He looked at her, expressionless.

“What does that have to do with…” A horrible realization dawned.

“Quick, this one,” laughed one of the men.

“We keep your sister,” Southack said. “You get on Bonny’s ship and report her movements to us. We capture her, you go free. Refuse, and you and Ruth go to prison. Take the deal, save your sister.”

“What do you know about Anne Bonny?” Rachel asked.

The Shanty Man’s eyes narrowed.

“Now, why would a pretty little thing like you ask a question like that?”

“Just curious,” said Rachel.

“Girl knows about curiosity and cats, right?”

The captain came on deck, looked at the calm sea and the sails, and shouted orders. The Shanty Man started a new song.

Cape Cod girls ain’t got no combs

Heave away, heave away, haul away, haul away!

They comb their hair with codfish bones

We’re bound for Australia!

Heave away, me bully, bully boys

Heave away, heave away, haul away, haul away!

Heave away, and don’t you make a noise

We’re bound for Australia!

The sailors leapt to the lines and hauled, joining in the call and response. Rachel’s pulse rose, and she felt a strange pull toward the ropes as the ship gained speed.

“Feel it, dontcha?”

“What?”

“Power o’ the shanty. Don’t deny it.”

Rachel felt an intimate embarrassment, as if he’d caught her undressed. Undeterred, she tried again.

“What if I wanted to meet her? I have gold. Can you get me to Bonny?”

“Girl, if you got gold, I’m the King of England.”

“Not here, of course,” said Rachel. “In Carolina.”

The Shanty Man snorted. “You’ll be lucky to see Carolina alive. Just keep quiet.”

“Would you teach me one of your songs?” Rachel asked again.

“That cost more’n yer a-willin’ a pay. I’m not talkin’ ’bout coin.”

Rachel rolled her eyes. “I’ve got gold,” she insisted. “Tell me where you’re staying.”

The Shanty Man laughed. “You got gold, maybe I can get you Bonny.”

The sailors sang as they prepared the ship for arrival in Bath. The waters off the Outer Banks were known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic, and the men were glad to be quit of them.

I thought I heard the Old Man say

Leave her, Johnny, leave her

To go ashore and get your pay

And it’s time for us to leave her

Leave her, Johnny, leave her

Oh, leave her, Johnny, leave her

For the voyage is long and the winds don’t blow

And it’s time for us to leave her

Just before they docked, Rachel wheedled out of him where he was staying. She had no gold, just some coins the Governor’s men had given her. She’d improvise.

#

She’d won the knife from a Polynesian sailor in a back alley in Boston. He called himself John Kanaka. He was like a figure out of myth. Deep brown, massive, heavily tattooed, somehow strangely friendly. Myth or no, she needed to eat, and loaded dice were her friends now. He’d been unhappy to lose the knife but seemed honorable about it. Afraid he would take the knife back, she started backing away.

“There’s something you need to know about that knife,” he said.

#

It was dark, and the Shanty Man was right well drunk. He heard knocking at his door. He looked out his window and saw the girl from the ship, steely-eyed.

Well, now. What we got here?

“Come in, come in. You be a sight for sore eyes.”

“I told you I had gold,” she said. “I need to get to Anne Bonny.”

“I told you, you ain’t scared enough.” He smiled a savage grin. “Why shouldn’t I just kill you and take your gold?”

An evil-looking knife appeared in her left hand. “I may look helpless, but I’m not,” she said. “You have sea power. I have blood magic.”

He watched her warily.

“You, a witch?” he scoffed. “Strange enough, I was ’bout to take a job on that ship. Bonny needs a new Shanty Man. Old one gone an’ lost his nerve, his voice, damn near lost his life.”

“Take me with you.”

“I need my songbook and a barrel o’ rum I buried in the woods. You wanna come? You can dig.”

“Don’t you know the songs already?” Rachel asked.

“Oh, there’s more’n songs in that book. It’s got power, an’ something else Bonny’ll want.”

“What?”

“The songs got magic an’ the book has a map. She need both but don’t know ’bout neither.”

“Does she know about you?”

“Never met her. Heard from a mate she was lookin’ for a new Shanty Man, but she don’t know I’m coming.”

#

It was night. They were deep in the woods with one torch between them.

“I sing, you dig.”

His murder ballad gave her a frisson of fear. But it didn’t take long until she hit something. In the flickering light, she saw the top of a chest in the ground. She finished digging and pulled it up. She turned and saw the Shanty Man, knife in hand. He made an obscene motion with the knife.

“One more thing I want afore we go.”

Rachel was no virgin, and Southack had her sister. She probably would have gone along with it if he’d been a bit more polite or smelled a little better, but his breath and teeth revolted her. Her knife appeared in her hand and buried itself in his heart before she knew it.

The Shanty Man sank to the ground, uncomprehending. As she pulled the knife from his body, he met her eyes. She’d never killed before and her gut heaved.

Rachel willed her stomach to settle. With some unknown intuition, she gently pierced the skin of his forearm with the tip of her knife, right in the strangest tattoo. The tattoo writhed on his skin as if in pain. Slowly, it slithered from his arm and into the knife. The tattoos ran from his face, down his arm, and into the knife. The Shanty Man’s eyes went wide as he saw his tattoos disappearing. He fell dead at Rachel’s feet.

Bracing herself, Rachel gently stuck the knife in her right forearm.

Shock rippled through her mind as the Shanty Man’s knowledge of the sea bled into her—the wind, the waves, the tides, the mystery—and the songs. The tattoos flowed cold into her veins, onto her skin, spiraled up her forearm, and settled. Onto her face as well, she imagined. Southack’s voice echoed in her head.

Send a woman to catch a woman.

Who says a Shanty Man has to be a man?

References for public domain song evidence

Author Bio

Mark is the founder of Bookship, a social reading app where people build better relationships through books. Previously a tech startup executive, Mark lives in Hawaii, is a poor sailor, a worse Shanty Man, and an aspiring outrigger canoe paddler. He holds an M.S. in Mathematics. Click to visit Mark’s website.