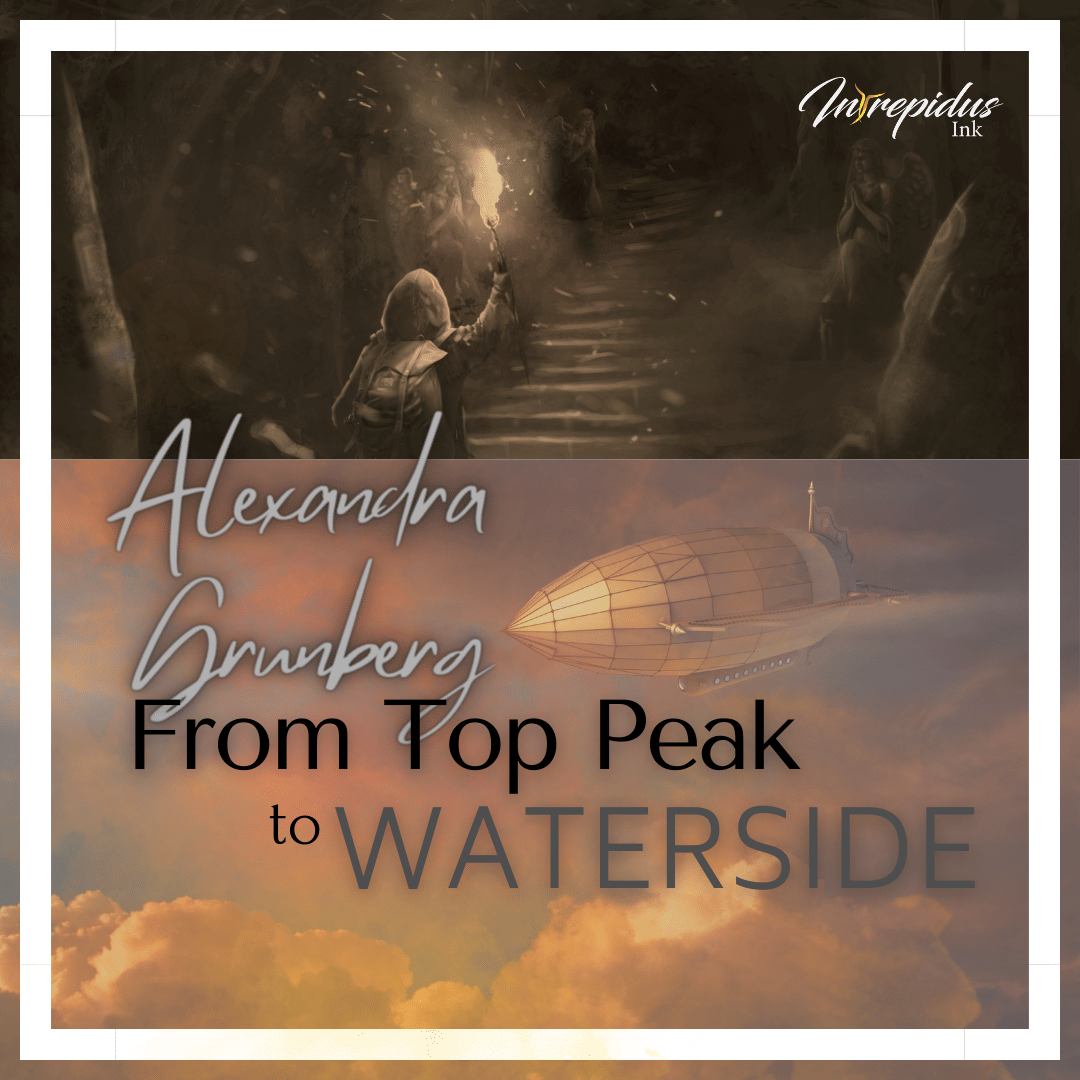

Speculative Fiction

E

very kid on the High Lines knew they weren’t supposed to play on the zeppelin tracks, but that was most of the fun for Diarmid and his brothers. Enough boys had died in the far drop to keep it thrilling. And the high of success was exhilarating enough to keep them coming back.

“Lachlan, it’s your turn,” said Diarmid, giving his youngest brother a none-too-friendly push towards the drop. “Tighten your strings and give it a good jump.”

Lachlan began tying his half-undone laces around his boot. He’d have to tuck in the long tail of his shirt, too, one of those old ones that must have belonged to Da.

“Naw, Diarmid, it’s too cloudy for the lil lad,” Bhatair said, shaking his head as he looked over the edge.

The zeppelins were the same dark grey as the clouds, giant whales wallowing in the air, carting the richest of Top Peak’s industrialists to their suburbs down in Waterside. The maintenance crews and their families lived in the shacks built into the thin scaffolding of the High Line, a criss-cross of metal supports that served as repair grounds for damaged vessels. Sometimes Diarmid saw the sons of the industrialists on the zeppelin balconies, all in their matching school uniforms, buttons shining through the smoke, whereas he worked on the scaffolding, his hands black with oil, eyes streaming from the steam.

“There’s no storms comin’,” Diarmid said before he spat as far as he could into the air, hoping it landed on some helpless fancy boy’s head. “Hardly a wind.”

“He cannae grip the rigging with those sausage fingers,” Ruiseart muttered from behind. “I’m ready for another go. If yous think yous can keep runnin’ the track.”

“No, it’s my turn!” Lachlan cried, his voice sure though his flapping tail belied his confidence. “I’ll no chicken oot this time, triple promise.”

There was a giant zeppelin coming in now, one of the branded ones, and Diarmid recognized it as one of their employer’s. They still got insurance pay-outs for Da stamped with that circle and cross, a symbol that was supposed to represent something like moving targets across the sky or expectations into the future. Looking forward instead of trailing behind.

“Why don’t we all do a jump?” Diarmid asked suddenly.

“What if one of us falls?” asked Bhatair, though he rolled up his wide sleeves.

“We cannae do anythin’ about it from up here, anyway.” Diarmid shrugged.

“Ma’ll be fumin’,” said Ruiseart, but he smiled as he said it, knotting his shirt.

“There’s a big un comin’ now.” Lachlan pointed and ran.

“Now?” Bhatair shouted, a smirk belying his groan as he raced to catch up.

Diarmid had already passed them and leapt into the air with a loud whoop while his three brothers followed behind.

It seemed impossible to hold on to those wide sides. It seemed inevitable they would slide down, screaming, the fall too far, the world too big. But four thwacks in succession and cheerful hollers of terror and glee told Diarmid they were all okay. They had all landed safely. Broken pieces of the zeppelin’s frame threatened to catch on their clothes, turning them into unwilling sails to be buffeted by the wind as the ship’s bulk streamlined through the clouds. It had carried away more than one child who leapt from the scaffolding. But not today.

Diarmid closed his eyes. The breeze forced tears across his cheeks, and he wondered if that was what the boys felt below, the ones in their shiny uniforms or if they were protected from the wind. The zeppelin shielded them from the harshness of Top Peak’s polluted skies, but Diarmid did not think he would trade the joy of his flight for the privilege of being locked within the monstrous machine. He could hear the tinny of voices already reporting the rogues to the conductor, but the boys would be off the second the zeppelin was close enough to the beach to fall safely. They would run across the sand, Diarmid and his brothers, laughing and in control. The ocean reached out to the horizon they rarely got to see, so impossibly far from the clouded skies they lived in, until they tied up their laces, took a steeling breath, and jumped.

Author Bio

Alexandra Grunberg is a Glasgow-based author, poet, and screenwriter. Over fifty of her short stories have been published in online magazines and anthologies. She earned an MLitt and DFA in Creative Writing from the University of Glasgow. You can learn more at her website, alexandragrunberg.weebly.com.