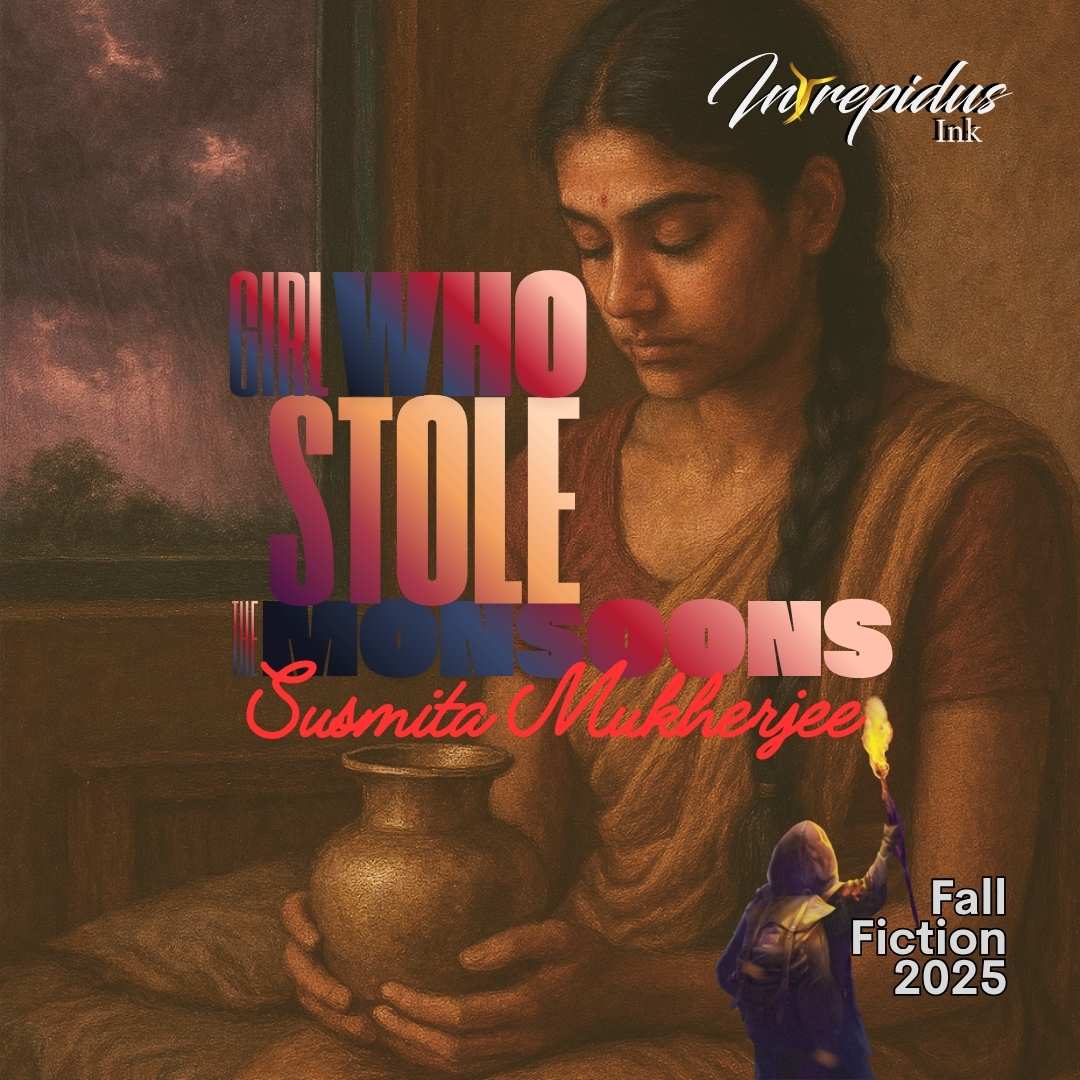

Magical Realism

I used to be a bird.

My mother never hid this fact from me. She told me as soon as I was old enough to understand. At the time, this made complete sense. Children are much more accepting of the impossible. I nodded as she prepared my breakfast, sunlight streaming through the window blinds and making bands of light on the kitchen table.

“Of course, Mommy,” I said, lips sticky with maple syrup.

I don’t think my mother understood how I came to be, but she wanted a baby so bad she didn’t question it. When your prayers are answered, even in the most impossible way, you just go with it.

My human mom was a good mom. She was better than good. Girl Scout leader, PTA member. Not to mention the best cook ever. And she talked to me. My friends’ moms only talked at my friends.

It wasn’t until I was older that she described the exact circumstances of how I turned into a human girl.

When my mom was a teenager, nineteen, I think, she got married. She didn’t tell me much about her husband, only that girls of her generation married earlier than they did now. Her husband turned out to be a bad man, but divorce wasn’t something anyone did.

He used to hit her, and when she eventually became pregnant, he beat her so badly that the baby died. The police arrested him, and she got a divorce after all.

The experience changed my mother. She lived alone and didn’t talk to other people. One day, she started watching birds outside her kitchen window. Then, she hung feeders and houses from the trees to attract more birds to the yard. She even bought binoculars and kept a journal of the species she observed.

One spring, she saw me on the ground in her backyard–a tiny baby bird fallen from its nest and abandoned by its mother.

A common starling.

She hurried outside, scooped me into a shoebox, and brought me back into the house. For days, my mother fed me every hour using a dropper until, early one morning, she came downstairs and found a human infant instead of a baby bird.

She named me Edith.

I never told my friends I used to be a bird. I always understood, like some unspoken code, that this was a secret between me and my mother. We were happy, and if other people found out I used to be a bird, they would take me away. My mother would be alone, sitting at the kitchen table eating pancakes by herself, with binoculars perched on her nose.

I grew into a girl with dark hair as soft as a bird’s down, and my nose was sharp and hooked, like a beak. The boys at school often made fun of my nose, calling me “Bird Girl.” Panic fluttered inside the cage around my heart. I was afraid they somehow found out my secret, but no, if they had known, the names they used would have been much, much worse.

Life as a human girl taught me that the world was equal parts gentle and terrible.

It must be simpler, I thought, to be a bird. And sometimes, I longed for it. When that happened, I went outside and collected feathers from our yard. Fallen from the birds, my mother still watched. I placed them, so many different shapes and sizes, in the same shoebox my mother had placed me, and on each, I made a wish.

I wished I could fly.

My mother told me about periods long before I had my first cycle. She explained the biology first, the reason my body would bleed, and the human feelings it would cause in me. Fear and also curiosity–the window I would have to pass through to become a woman.

So, I knew it would come.

I was in my room, reading about humans, about the world around me, trying to understand. I worried the boys would eventually catch on and realize that I was actually a bird girl. I thought the more knowledge I had, the longer I could fake being human.

There was a boy I liked, Jacob, from my homeroom class. Quiet and more reserved than the rest. The day before, he’d casually mentioned the upcoming dance to me.

Would I like to go with him?

Yes, I would.

My mother, however, was appalled at the idea.

“But Jacob is nice,” I insisted. He never called me “Bird Girl” and thought my feather collection was interesting.

“All boys are nice…at first.” She sat with the binoculars glued to her face. Birds swooped by the window in flashes of brown, blue, and red.

“I want to go.”

“I’m sorry, Edith. I won’t allow it.”

My mother and I rarely argued, but Jacob’s shy smile swooped into my mind, so I continued to push.

“I’m growing up,” I said. “You have to trust me.”

She lowered the binoculars. “I do trust you. But other people?”

“You can’t keep me locked in here like some kind of cage.”

My mother stared at me for a long time. Finally, she nodded.

I opened my bedroom window.

My insides cramped, and my underwear dampened. Without looking, I knew my pants would be bright red, like cardinal feathers on snow.

A spring breeze teased my hair. I lifted my arms and wiggled my fingers, welcoming the wind and whatever would come next.

“Thank you, Mom,” I whispered and rose into the air.

A young bird ready to leave the nest.

I looked outside, at the ground two stories below.

I was ready to fly.

Author Bio

Heather Santo is a procurement lead living in Pittsburgh, PA with her husband and daughter. In addition to writing, her creative interests include photography, painting, and collecting skeleton keys. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter @Heather52384, and visit her on FaceBook.